My

project of collecting brand attitudes revealed something interesting -- and egocentric -- about the way we relate to advertised brands. Several of my friends and colleagues volunteered their time and responded to the

brand attitude scales.

And although this is just a thought exercise, some interesting patterns appeared. Dating back to

1957, researchers have employed the

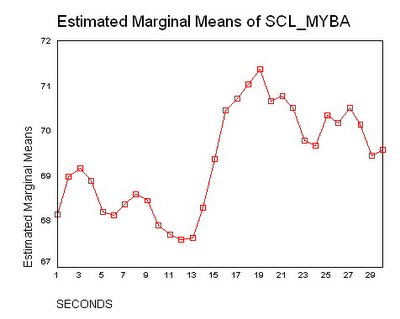

semantic differential to assess how meaning is represented. Without being overly technical here, you can ask people to indicate their perception of a given thing X by choosing a point between a pair of adjectives (e.g., good _:_:_:_:_:_:_ bad). Osgood et al. asked 50 such pairs. I used 30. Then you can use a statistical technique called factor analysis to find a smaller number of orthogonal dimensions (i.e., roughly speaking this means they are not correlated). That is, you can examine whether 30 unique factors drive the responses, or a smaller number.

Not surprisingly, in many, many studies, a common factor appears to drive responses to similar adjective pairs such as good-bad and pleasant-unpleasant. Furthermore, many studies have shown that a different, uncorrelated factor drives responses to adjective pairs such as arousing-calm and active-passive. Finally another factor typically emerges that captures responding to pairs such as in control-out of control. Osgood et al. (1957) labeled these dimensions evaluation, activity, and potency. As mentioned here before, we call them valence, arousal, and dominance.

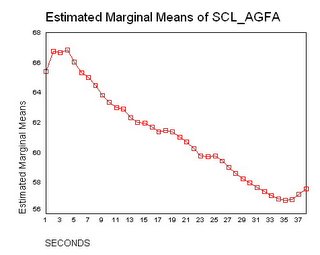

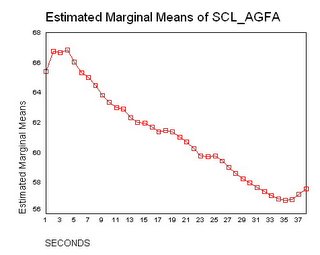

These three dimensions have captured the pattern of responses to numerous types of stimuli. My simple question is whether these dimensions apply to brands. In short, they appear to. But a far more interesting finding emerged from this thought exercise. In addition to the traditional semantic differentials, I included measures of "identification" such as mine-other's and like me-not like me. What drives

these responses?

Although I expected the identification responses to be correlated with the valence measures (i.e., similar to me is a good thing), I was nonetheless surprised by the magnitude of the relationship. The measures of identification behaved

identically to the measures of valence. If it was good, it was like me. If it was

not like me, it was unpleasant, bad, not likable, and troubling. If it was good, pleasant, likable, and comforting, it was

mine.

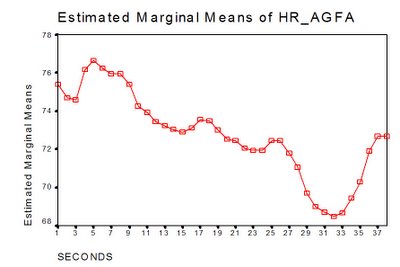

I started this project with the vague notion that we treat brands like people. We associate personalities with them, and we identify with them. Sure, we may say that

Pepsi tastes better, but it is more than that. If you insult Pepsi, you are doing more than insulting something that I like. You are insulting something that is like me. You are, in essence, insulting me.

Saatchi & Saatchi CEO Kevin Roberts was

onto something when he talked about brand relationships that transcend reason (see the Frontline documentary,

The Persuaders). This project in the Communication & Cognition lab is quickly moving from journalistic exercise to formal science. The application to conduct systematic research with actual human subjects will be filed this week, and we should begin collecting research data in early February. Stay tuned.